Man imprisoned for thirty years, still says he's innocent ... Major Discrepancies Found in Thirty Year Old Case

By Shaz Sajadi, Karine Choi, and Evelyn Martinez

It was 10:30 p.m. on a drizzly November night in 1985 when a group of five left a Brockton bar and got into their car.

They’d been partying at Pete and Mary’s, a local bar and popular hangout spot for many young people at the time.

Among them were Walter “Bo Bo” Watson, Edna Levine and Terri Lynn Starks in the front seat. Lisa Pina and Alfred Moreau sat in the back.

Nearby, a couple sat in their car eating subs; Denise Perkins and Paul Jones.

Within minutes, shocking all, a tall Cuban man named Guillermo Rodriguez was shot dead.

But when each of them recounted the startling events of that night in the D’Angelo parking lot, many of their stories differed. Yet despite this, their interviews with police led to the conviction of then 18-year-old Darrell Jones, who has steadfastly claimed he is innocent of the crime.

Now Jones is appealing his conviction for the fourth time, seeking to reopen the case based partly on faculty eyewitness testimony with the help of the Innocence Project, a nonprofit organization which works to overturn cases of people they believe are wrongfully convicted. The Commonwealth’s case against Jones solely relied on eyewitness accounts. But none of the eyewitnesses pointed out Jones in court.

A four-month investigation by Emerson College students found inconsistencies in the testimony to be one of multiple problems with the 30-year-old case. Students read through court documents, interviewed specialists and investigated the scene of the crime. Among findings, students found six major discrepancies in witnesses testimony that raise questions about whether Jones received a fair trial. Other findings include:

- Vernell Dukes was Darrell Jones’s alibi for the time of the shooting.

- Evelyn Anderson was another alibi for Darrell Jones for the time of the shooting.

- Intoxicated Eyewitnesses

- Cross Racial Identification

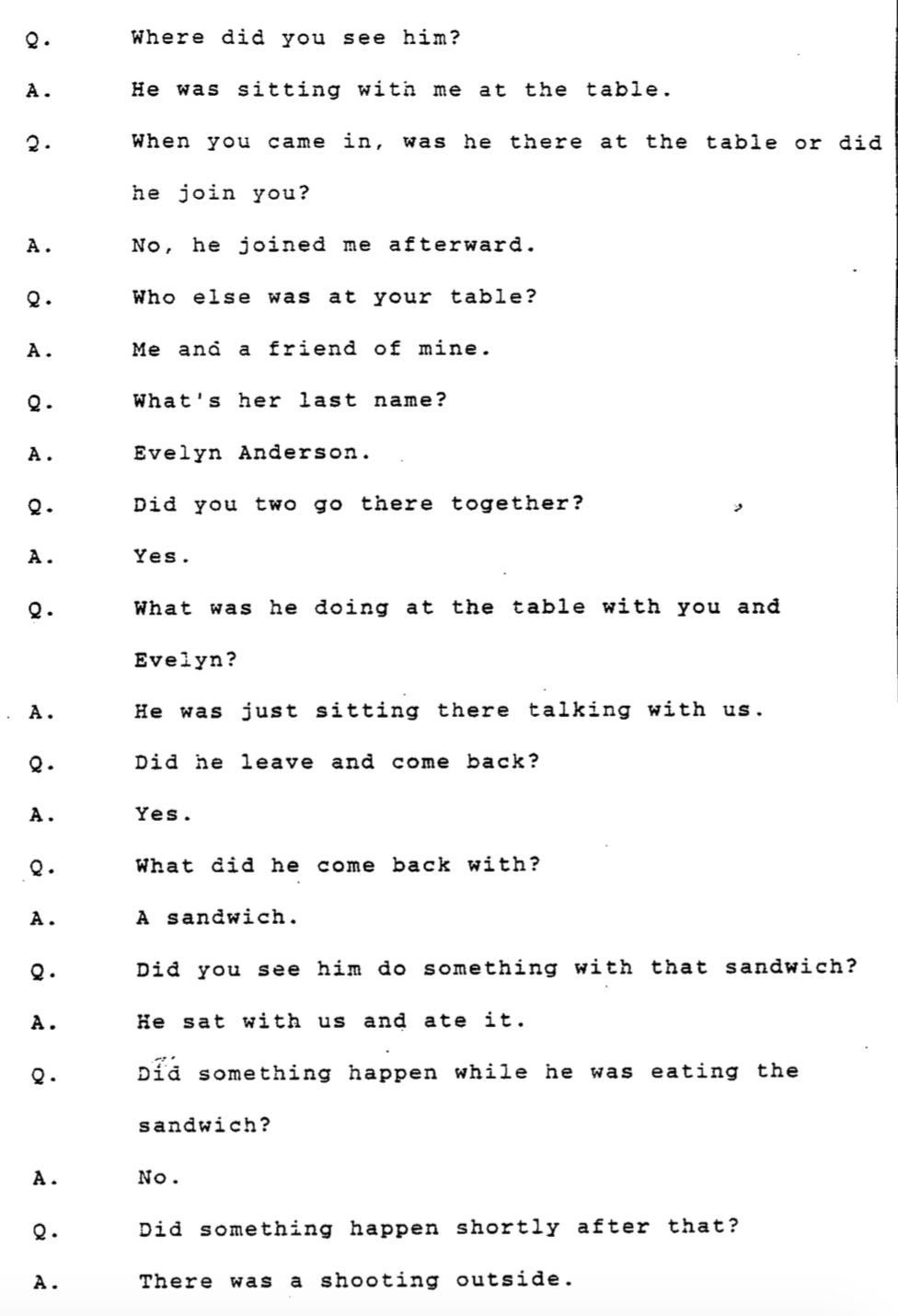

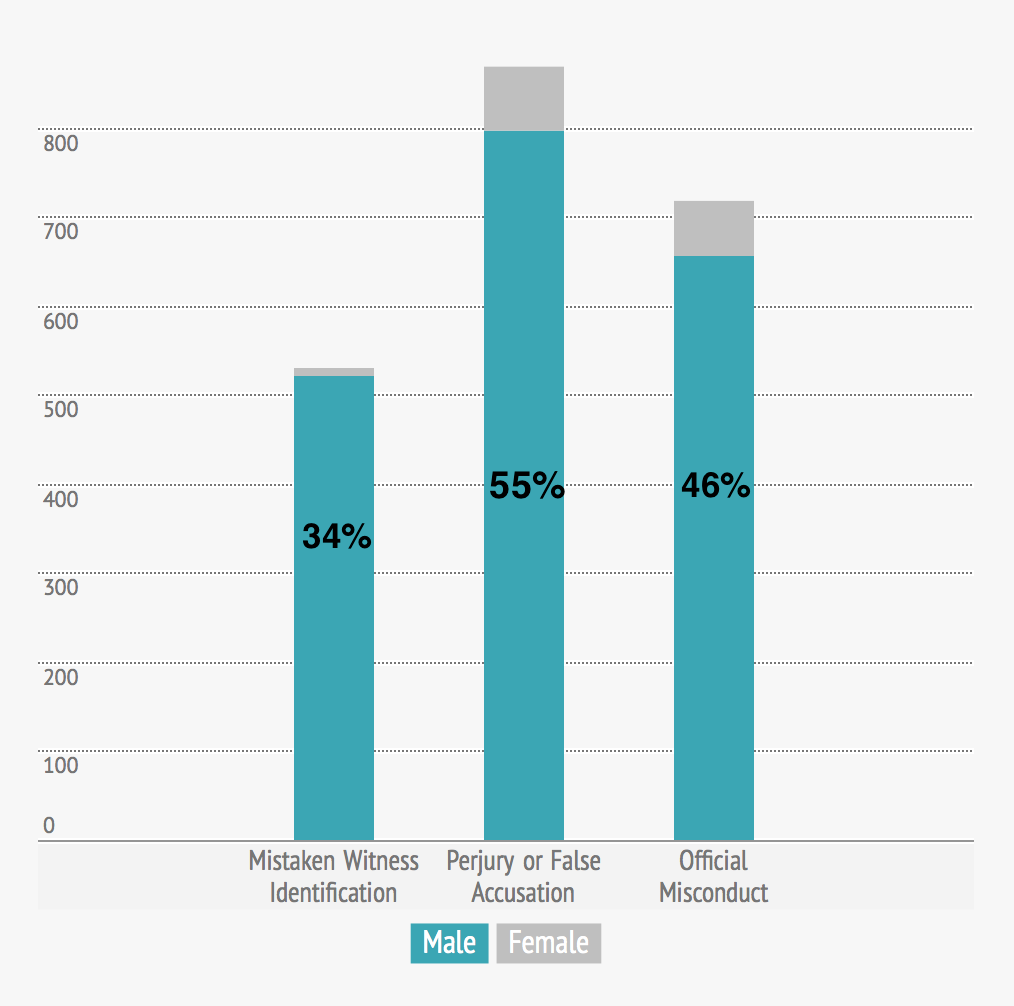

Vernell Dukes, a friend who was at the bar that night, testified that Jones spent the night in the company of her and Evelyn Anderson. She testified he left the bar and came back with a sub and when he came back he just sat down and ate it, nothing else happened. The shooting happened sometime after he came back with the sub and when the police came into the bar to alert everyone.

Evelyn Anderson was another friend who was also present at the table with Dukes when Jones joined them with his sub.

It is true that Dukes and Jones did not spend the whole night at the bar together, but she and Anderson both testified he was sitting with them eating his sub until the police came in. Perkins and Paul Jones saw Darrell Jones going to D’Angelo and coming back to the bar with a sub. Dukes and Anderson testified Jones never left again until after the shooting.

The District Attorney Kevan Cunningham discredited Jones’s alibis’ testimonies on the point that they had had some drinks at home before going to the bar, but all of the five eyewitnesses in Watson’s car had also had drinks. Cunningham built his case against Jones on the testimonies of people most of whom had come out of a bar after a night of drinking.

six man photo array

Perkins and Paul Jones identified Darrell Jones in two ways.

They identified the man who went into D’Angelo with another woman by the name of Brigite Strothers and bought a sub as the shooter. Darrell Jones confirms going with Strothers to D’Angelo and getting the sub.

They also identified the shooter by picking out Darrell Jones from the police picture array. They testified that Jones’s picture had the closest resemblance to the person who did it, but were not 100 percent sure.

They also refused to identify Jones as the shooter in court.

According to Mistaken Identification: The Eyewitness, Psychology and the Law by Brian L. Cutler and Steven D. Penrod says, “Undoubtedly, the cross-racial identification problem is both more compelling and more widely misunderstood than other types of misidentification. According to Rethinking Reliance on Eyewitness Confidence by Patrick M. Wall, A crucial “factor to be considered in assessing the reliability of any identification is whether the witness and the person identified are of the same or different races.”

To educate the jurors and the court on the limitations of memory and the human sight, attorneys call in psychologists and eyewitness experts “to present their research during trial where the eyewitness identification is the sole or primary evidence against the defendant,” says Gary Wells, PhD a psychology professor at Iowa State University.

Dr. Paul Michel, eyewitness expert specializing in eyewitness identification and eyewitness testimony regarding false identification and threat assessment says “An eyewitness identification is when someone says out of the 7 billion people in the world, it was him, not someone who looks like him, not his twin brother who has a scar on his cheek.”

He also pointed out that it is very important for the eyewitnesses to see the person who did it from the same angle where the incident occurred.

The picture above, a frontal picture of Jones, was shown to the eyewitnesses for identification. However each witness observed the crime scene and the suspect at different angles.

Michel says, “That may be your case right there. It is almost impossible to identify someone you saw for a few seconds with a picture taken at a different angle.”

First Chapter: Discrepancies

The court transcripts show at least six major discrepancies between the witnesses.

The only witness who linked Jones–by name–to the scene was Terri Lynn Starks. Starks was a prostitute in Brockton who regulated Pete and Mary’s. She did not know Jones personally. In her testimony Starks said that Levine, who was also in the car, named Jones as the shooter. But in Levine’s testimony she said she never looked at the suspect. Instead she accused Starks of having said Darrell Jones’s name in the car.

“Eyewitness memory is not film,” said James Doyle, Boston attorney and co-author of Eyewitness Testimony: Civil and Criminal, “if memory were like a videotape you wouldn’t remember the wrong thing.” The problem with eyewitness testimony–and why it is unreliable– according to Doyle, is that memory is vulnerable and malleable. Witnessed events do not playback in the mind as they occurred.

The District Attorney used Starks’s interview as evidence against Jones, but Starks did not identify Jones in court and the videotape of her interview with the police was taped over at the point where she is asked to identify the shooter.

She was in custody at the time of her interview.

Another inconsistency was found in the court transcripts regarding Darrell Jones’s nickname, “Diamond”. Some of the witnesses knew him only as Darrell Jones and some knew him only as Diamond. The only instance Darrell Jones was named on the night of November 11, 1985 was when someone mentioned his name or nickname in Walter Watson’s car.

There are disputes on who said the name and what name was used, but both groups of witness thought of the same person by hearing that one name.

The testimonies regarding the gun was another discrepancy in the eyewitnesses’ memories in this case. Two of the witnesses, Perkins and Paul Jones testified that they saw the victim fly when shot, but according to firearm expert, Ron Scott, it would be impossible for a person to fly when hit by a handgun especially one with a .32 caliber which was the gun that was used on November 11, 1985.

None of the witnesses recall hearing the gun go off that night. According to Scott, all the witnesses were close enough to hear this particular type of gun. This shows how people hear and see different things.

Perkins and the investigating officer who interviewed her, Donald Legarde, have different recollections of the interviews. She remembers narrowing down the array of photos to four suspects the first time she was interviewed. Then she picked out Jones on the second interview, while never being 100 percent sure. Legarde mentioned in court that he remembers Perkins pointed out Jones’s picture in the first interview. He remembers her being very sure about it.

In the case of Darrell Jones, the inconsistencies in the testimonies of the witnesses were noticeable. Detective Joseph Smith of the Brockton Police Department had been interviewing witnesses for 20 years. He commented on the discrepancies of this case in trial. “The witnesses in this case have a tendency to be very forgetful and change their testimony…”

According to Accuracy of Eyewitness Memory for Persons Encountered During Exposure to Highly Intense Stress by Charles A. Morgan III, “High levels of stress or fear can have a negative effect on a witness's ability to make accurate identifications. Although moderate amounts of stress may improve focus in some circumstances, research shows that high levels of stress significantly impair a witness's ability to recognize faces and encode details into memory.”

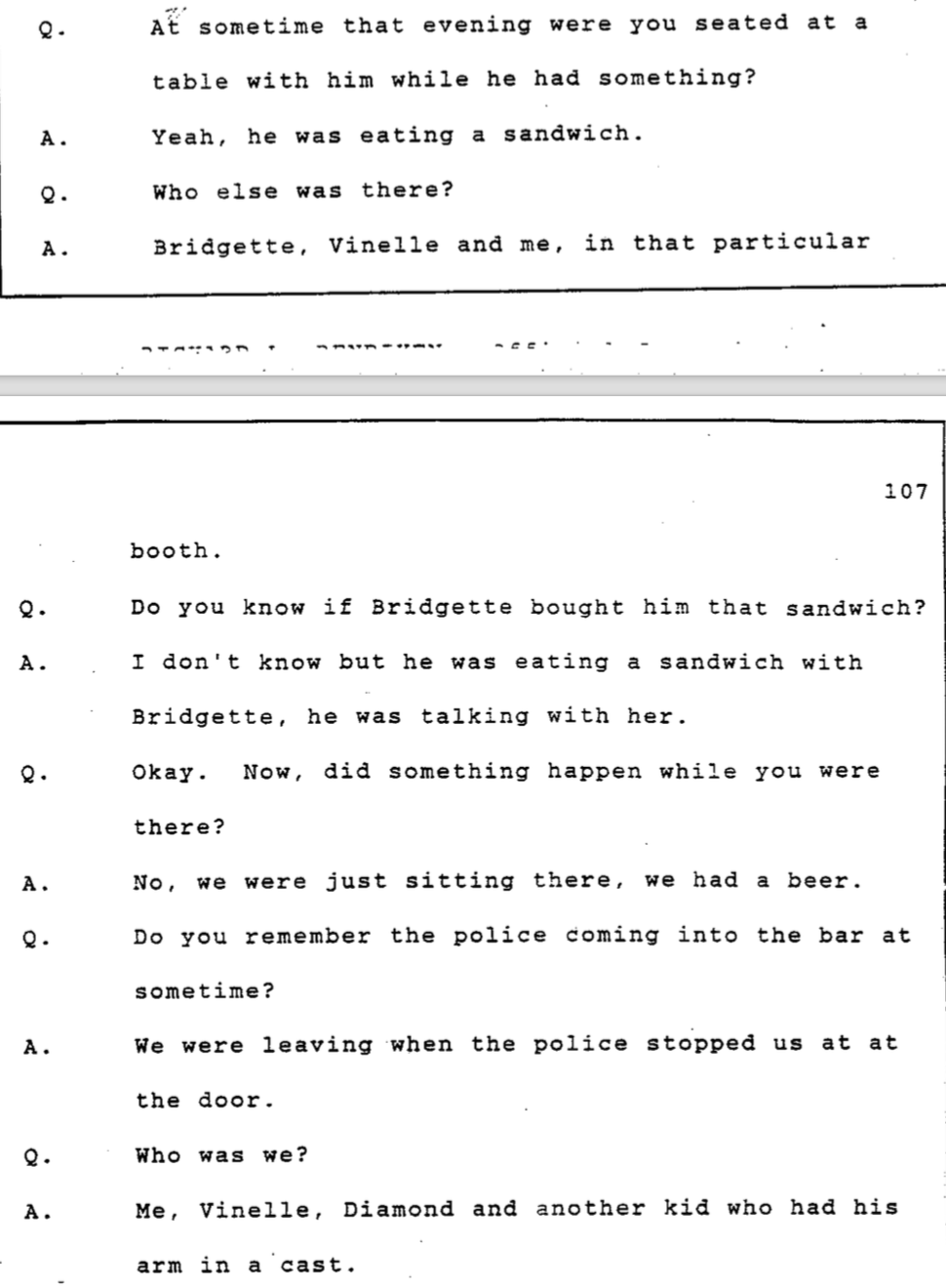

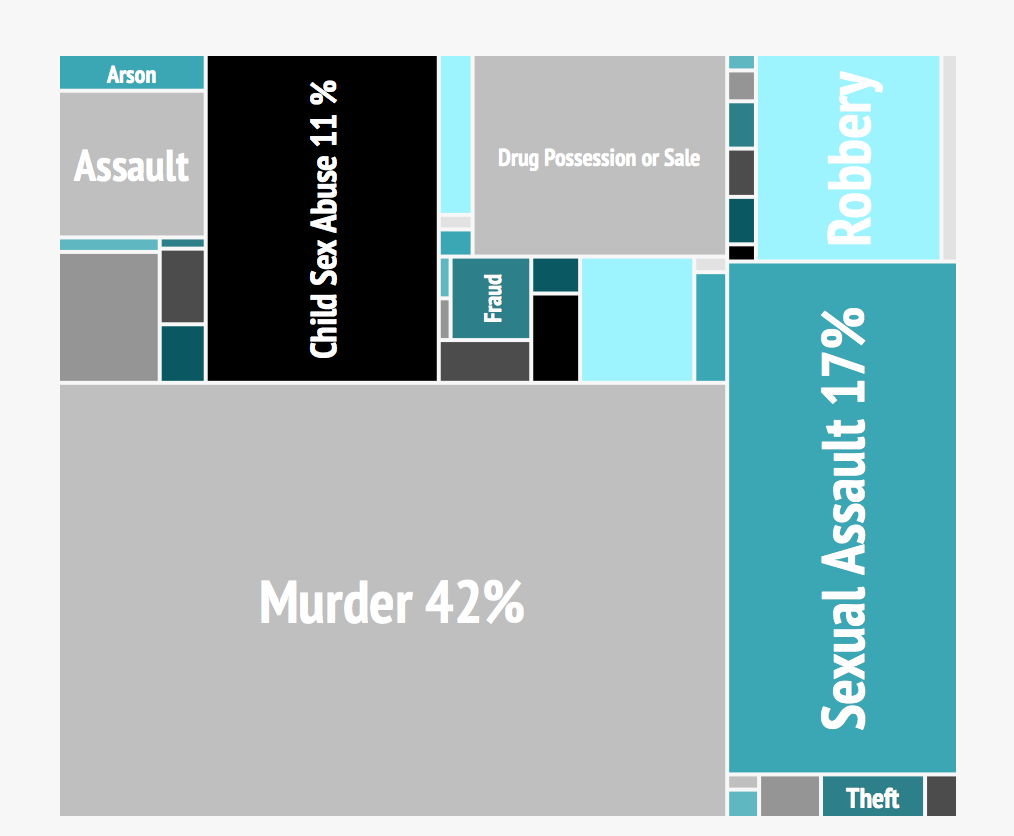

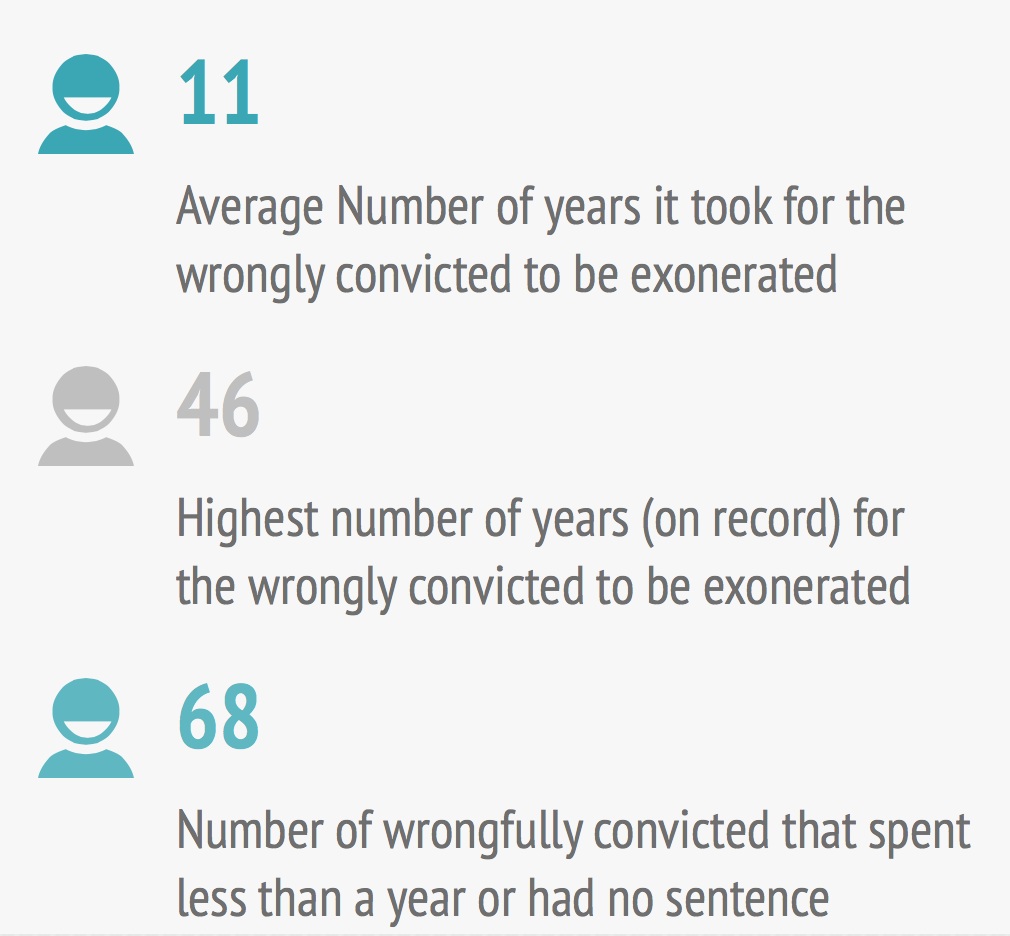

Roughly one third of the exonerations were based at least in part because of mistaken eyewitness identification, according to The National Registration of Exonerations. Most of the total number of exonerations also included official misconduct, perjury or false accusations, says Kaitlin Jackson a research fellow for the National Registration of Exonerations.

A total of 1,578 innocent men and women have been wrongly convicted of crimes in the United States. This number continues to increase as more courts exonerate the wrongfully convicted. The National Registration of Exonerations provides a detailed data record on every known exoneration since 1989. This database lists all the contributing factors of why the individual was wrongfully convicted.

The leading three factors in wrongfully convicted felons are perjury or false accusation, official misconduct and mistaken witness identification. Perjury or false accusation is 55% of the contributing factors of wrongful convictions. Perjury is when witnesses or testimonies are lying under oath or makes false statements in legal situations. The second leading factor is official misconduct, which is a crime a government official or a public servant can commit by violating his/her duty to follow the law and act behalf of the public good. Mistaken witness identification comes in third with 34%.

Second Chapter: Identification Issues

Elizabeth Loftus, a psychological scientist who studies false memories, said in her Ted Talk in 2013 that “memories are constructive and reconstructive they work more like a wikipedia page–you can go in there and change it, but so can other people.”

But memories can be altered unintentionally, said Loftus. Speaking to other eyewitnesses or the police, alcohol and time can manipulate a person’s recollection about the sequence of events which can contribute to false memories. Perception, the way we understand the world around us, also affects how memories are formed and interpreted.

Five of the seven people who had witnessed the shooting had been drinking in Pete and Mary’s bar according to their own testimonies.

According to “Intoxicated Witnesses” a research study done at Kingston University in London and the University of Abertay in Dundee, “Alcohol produced no effects on either the total amount of information recalled or the number of accurate central details reported. However, alcohol reduced the recall accuracy of peripheral details, suggesting that it may have narrowed attention to central details.”

Most of the witnesses in this case agreed on the main events on that night, a tall Cuban man was shot by a shorter black man. What they didn’t agree on, were the details.

“Confidence of witness is not well related to accuracy of witness,” said Doyle, but in the case of Darrell Jones the witnesses were not confident that they could point out the person they saw shoot Guillermo Rodriguez on November 11, 1985.

In fact, not a single witness could confirm that Jones was the same person they saw kill Rodriguez in court nor could they confidently pick out a picture from the array of pictures they were shown by police. Some Remembered a man holding a gun others described him drawing it at the last minute.

“Stress impairs memory,” said Doyle. But he warns that wrongful convictions are “multi-causal” and cannot be solely blamed on faulty eyewitness testimony. “You can’t blame it on one thing–you’ll find little things. Many little mistakes equal organizational dysfunction.”

Lisa Pina, one of the witnesses said she was crying when she picked out Jones’s picture. She said in court she was “under pressure by the rude police officer” to pick a picture.

Third Chapter: Status of the Case

Attempts to reach Miko Brown, the last person known to talk to Guillermo Rodriguez, were unsuccessful, despite three trips to Brockton, extensive outreach to neighbors, public records and social media.

At one visit to Vernell Dukes’s last known address, voices were heard behind the door, but no one answered.

Other attempts to reach regulars at Pete and Mary’s were thwarted by the fact that the bar was resold several times.

Jeffrey Summers, a former owner of Pete and Mary’s said in an interview, “I renovated the bar so that I would get rid of the previous crowd that regulated the place.”

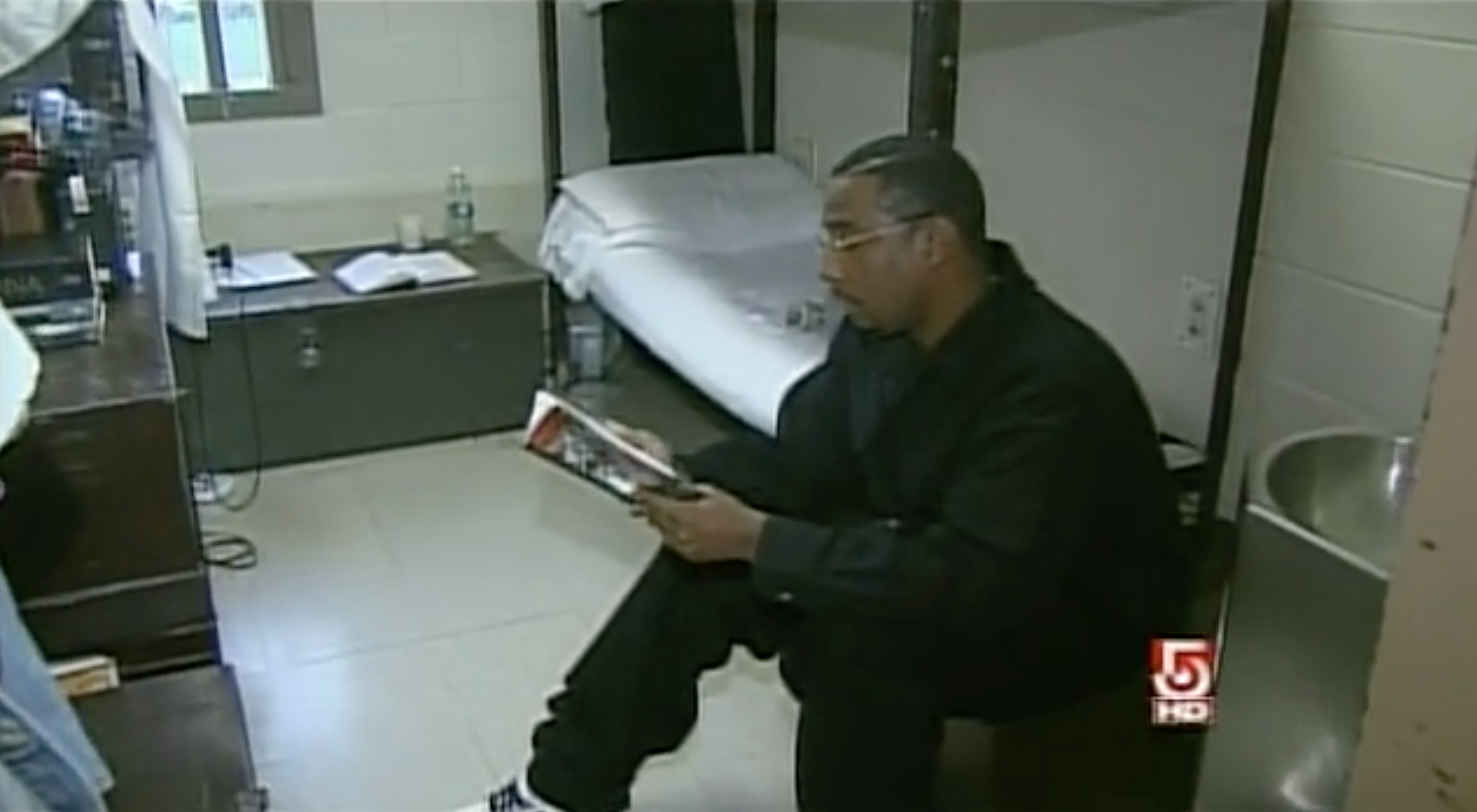

Darrell Jones is currently in prison at the Massachusetts Correctional Institution in Shirley. He has maintained his claim of innocence throughout these thirty years and has been actively involved in raising awareness on violence inside prisons and on the streets of low income areas. Through these activities, he met his wife Joanna Marinova.

UPDATES: Pictures from the crime scene (2015) in Brockton